Would you like a personalized list of plants that will thrive while attracting pollinators? Learn how to create one using online resources from the comfort of your own home and save a lot of money, time, and resources.

What’s wrong with buying garden books?

Nothing: They’re a good place to start. However, even books discussing Texas native plants are less than ideal for building your pollinator garden. For example, a recent read regarding Texas native plants used by native butterflies for larval hosting was helpful, but insufficient for two main reasons:

• The authors featured only 100 plants out of thousands.

• A good portion of their suggested plants are not native our local area, making them less likely to perform well in my garden.

Authors deserve compensation for their time, effort, and expertise, but publisher’s expectations, space limitations, and the need to focus subject matter leave you with less useful information. You can become your own local expert by creating more comprehensive plant species lists for your pollinator haven.

Performing basic search according to your needs.

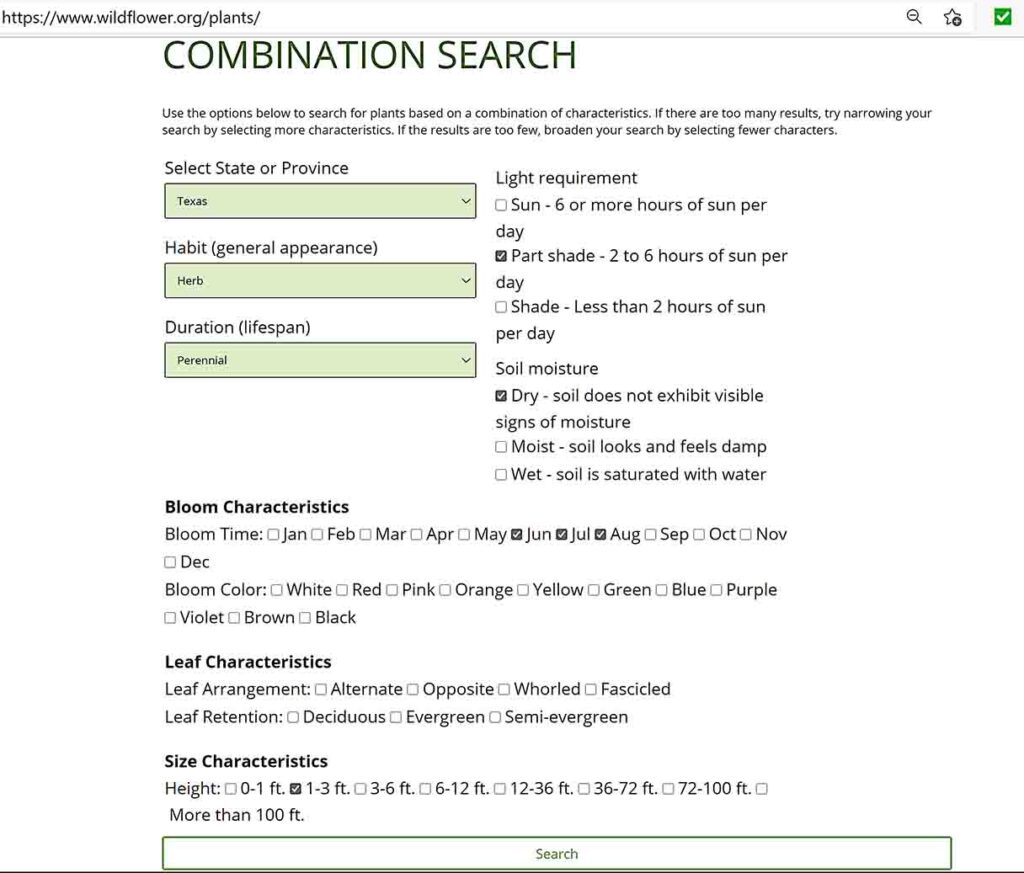

Let’s say you want to find hardy native perennials for beds beneath the high shade of established trees that get some morning sun. First, navigate to the Lady Bird Johnson native plant database at https://www.wildflower.org/plants. Notice that you can select criteria below “Combination Search” to narrow your search. Select for plants native to Texas (“Select State or Province”) that are herbs (“Habit”), which in this case means plants that don’t form persisting woody stems like deciduous shrubs. Select “perennial” (“Duration”) because you want true perennials: plants that grow back from their roots each spring. Also select for plants that handle part shade and dry soil, because those are usually tough, low-maintenance plants. To narrow the search further, ask for plants that are 1–3 feet tall when mature (check the “1-3 ft.” box under “Size Characteristics”). You’re searching for understory plants that don’t visually detract from stately trunks of established trees. Planning a perennial garden that offers beauty and nectar throughout the season is a win for all; include plants with varying bloom periods to reach this goal. Lady Bird’s original “combination search” includes “Bloom Time” in its “Bloom Characteristics” section to help create a progression of nectar sources throughout the growing season. Select July and August to see which plants offer nectar during the hottest season.

(There are other search criteria lower on the page if you want to further refine your search.)

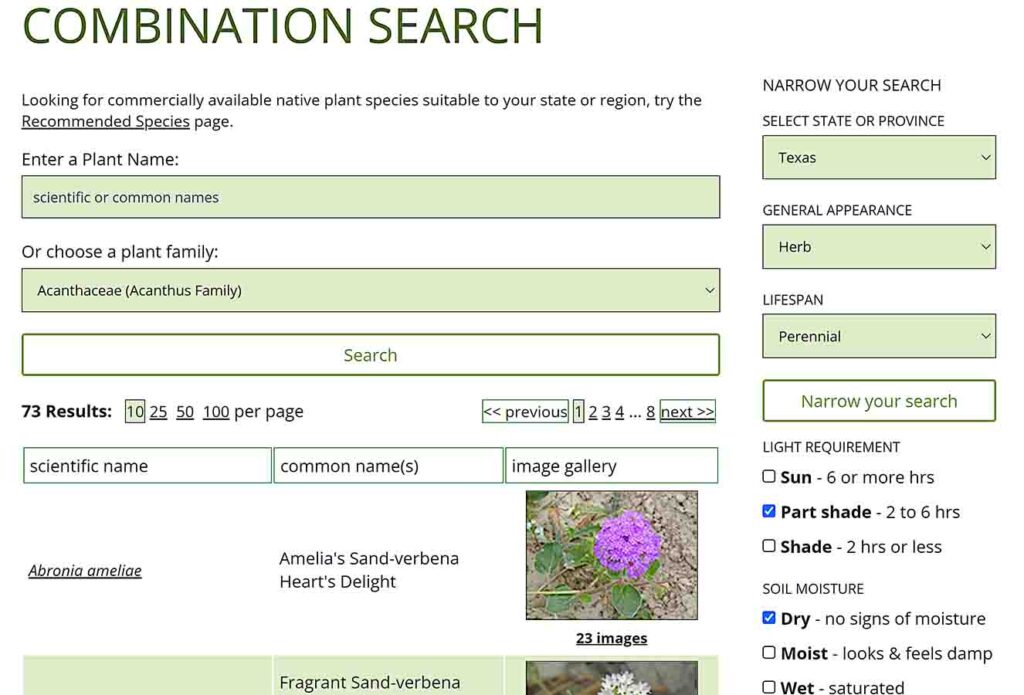

Clicking the “Search” button returns over 70 possible plants. That may seem like too many. Authors get paid to winnow down raw data into manageable, book-sized discussions; here’s how to easily do it yourself.

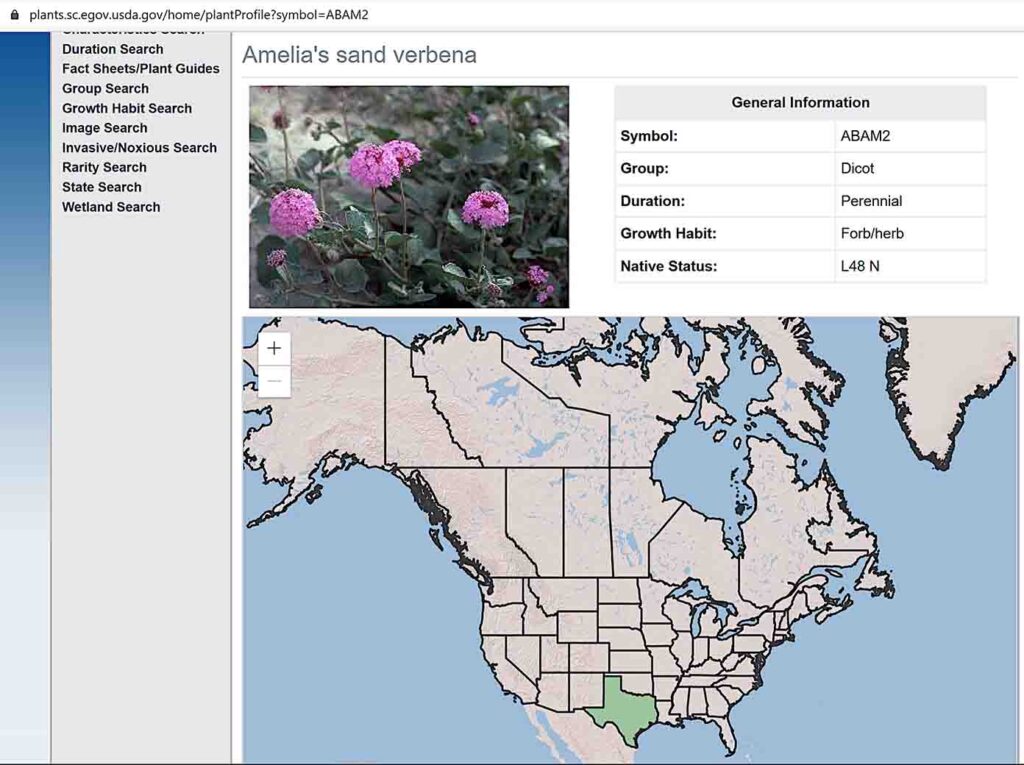

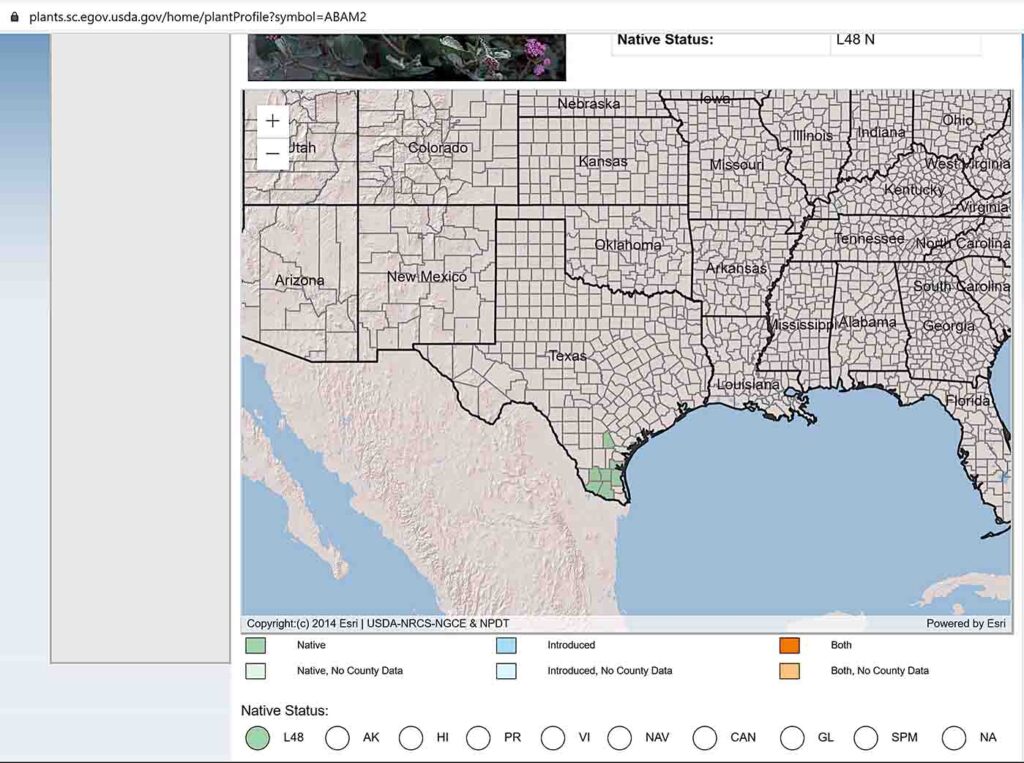

The next step is to determine which of these plants are native to your county. There are two reasons for doing this. First, plants in your county are most likely to thrive with the least amount of work and resources on your part. Second, pollinators residing in your county are more likely to recognize natives for nectar and larval hosting. Navigate to the USDA Plants Database at https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/home/. For each plant on your Lady Bird search results, copy and paste the botanical name into the search box in the upper left of the USDA database. In this search, the first plant is Abronia ameliae. Click on the “Go” button to return information on this plant.

USDA shows that Abronia ameliae is native only to Texas. On the map’s left are zoom buttons. If your mouse has a scroll wheel, rolling it forward while your cursor hovers over the map expands the map until county details appear. After zooming in, we see that Abronia ameliae is native to South Texas. If you live elsewhere, return to Lady Bird results. Repeat the above USDA search until you find plants native to your county.

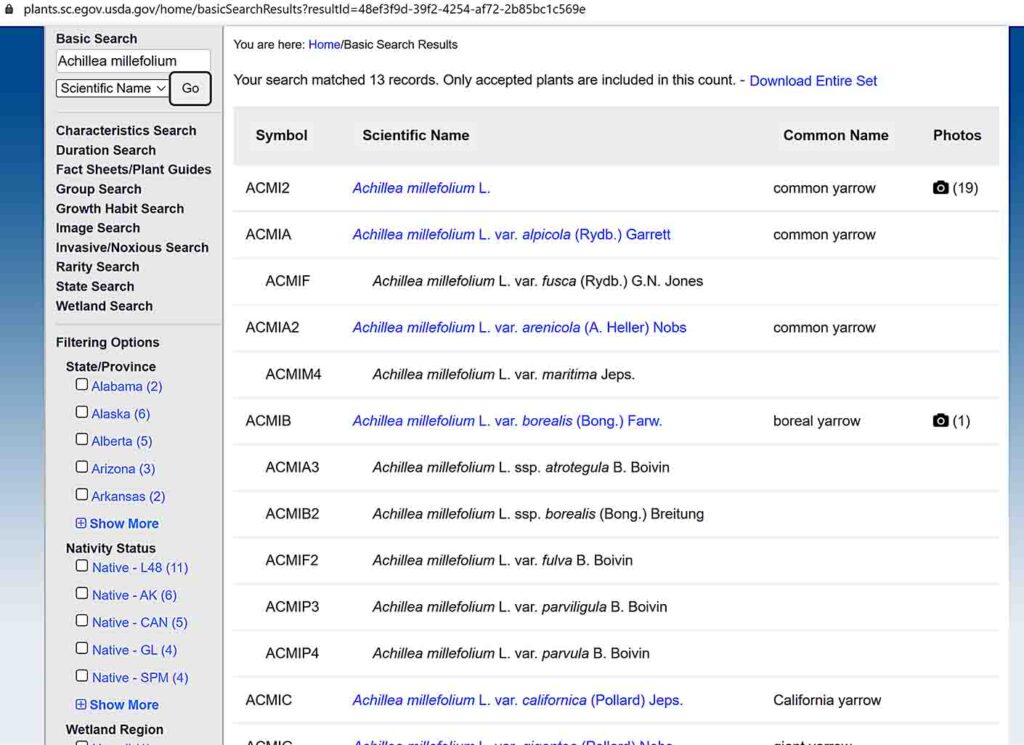

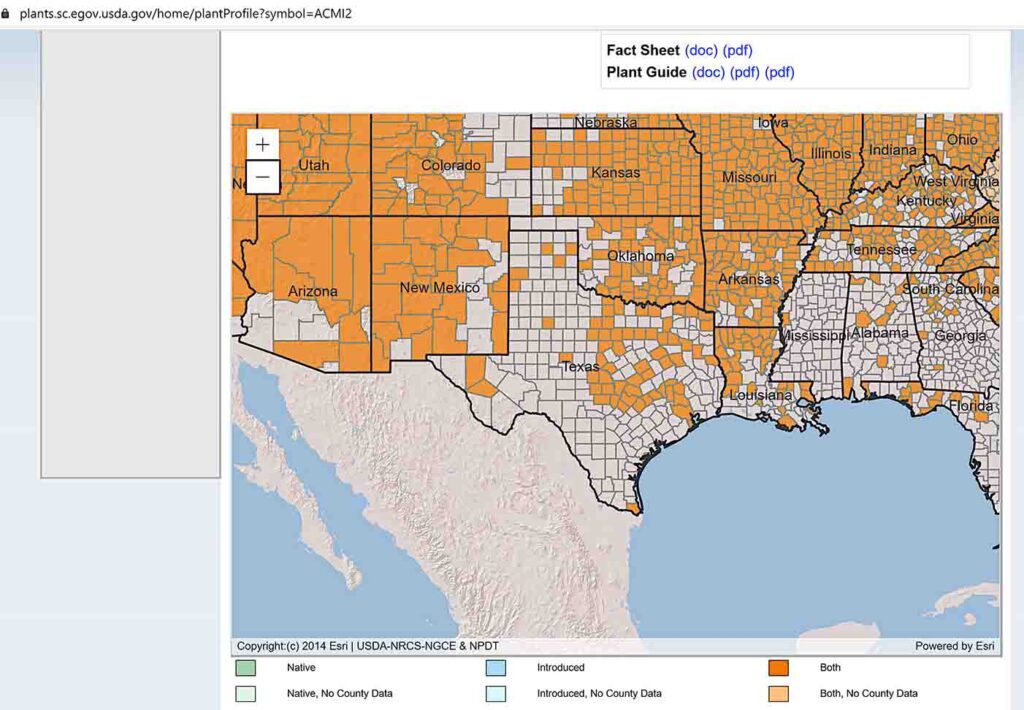

For this lesson, skip down to Achillea millefolium. Categories aren’t always straightforward in these searches. The first result USDA displays is a list of the species, subspecies, and varieties of Achillea millefolium. Select the species, conveniently first on the list. After clicking on it, you’ll see that the USDA considers Achillea millefolium both native and introduced in Texas. Fortunately, it’s native to many Texas counties. Also, notice that some USDA plant pages include a “Fact Sheet” and “Plant Guide” (upper right of screen). These provide details that will help you be more successful when growing this plant.

Returning to Lady Bird, click on the Achillea millefolium hyperlink to learn more about the plant, helping you decide if you want it in your landscape plan (https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=ACMI2). Lady Bird includes a general description, plant characteristics, and other criteria like bloom color and time. Scrolling towards the bottom, Lady Bird includes relevant pollinator information: Under “Value to Beneficial Insects” we learn that Achillea millefolium offers “special value to native bees.” A native plant that offers “special value” to native pollinators is notable.

If it’s native to your county, list it in a table. Spreadsheet and word processing software are great organizing tools. Populating this list is your first step in the process. I usually include columns for botanical name, the link to Lady Bird’s page for this species, and bloom period.

Larval host plants create a full-time butterfly home.

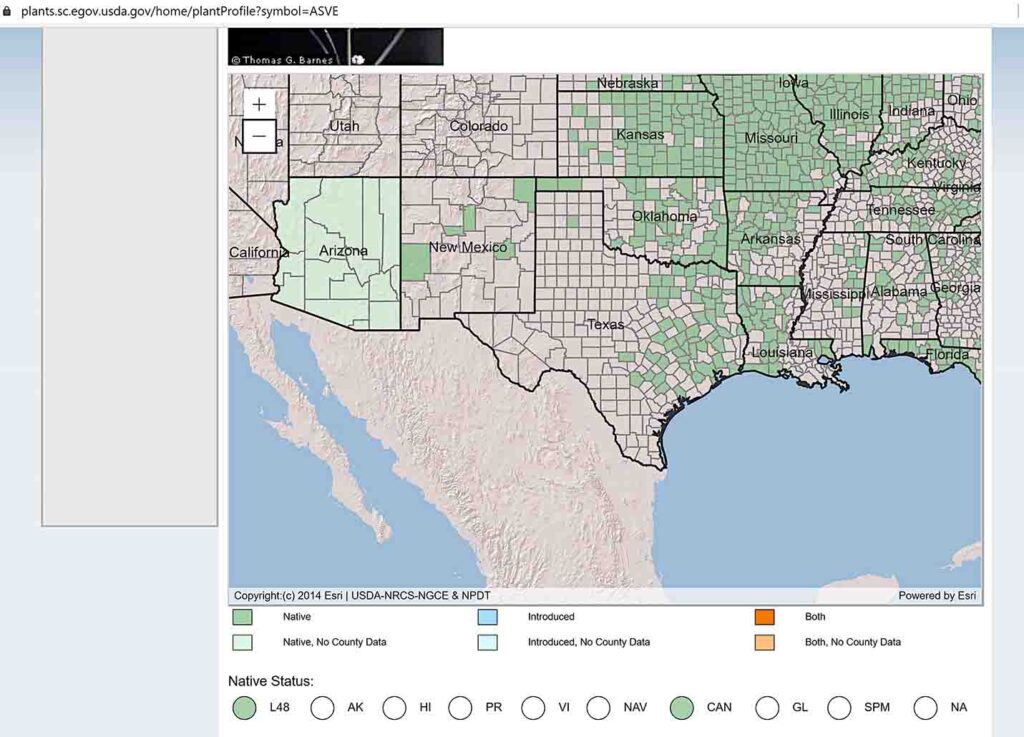

Other native plants offer larval hosting for butterflies and moths. Including host plants creates a garden that provides a home throughout their entire lifecycle. For example, the milkweed Asclepias verticillata is native to many counties in the eastern section of Central Texas (https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ASVE). As we all know, it’s a host plant for Monarch butterflies, making it worth cultivating in semi-shady areas. Better yet, we have native butterflies—living in Texas their entire lifecycle—that use milkweed to feed their young. This brings us to the next piece in your list-building process.

If butterfly gardening interests you, first perform an internet search of “butterflies milkweed” to obtain results like this University of Florida article that list other butterflies—Queen and Soldier—whose larvae need milkweed (https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/ornamentals/milkweed.html). Searching for “butterflies/caterpillars [plant name]” enables you to find butterflies that need a certain plant for larval hosting or not, as each case may be.

Next, familiarize yourself with Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) at https://www.butterfliesandmoths.org. As with Lady Bird and USDA, there’s a search box in the top right of their home page, enabling you to look up butterflies.

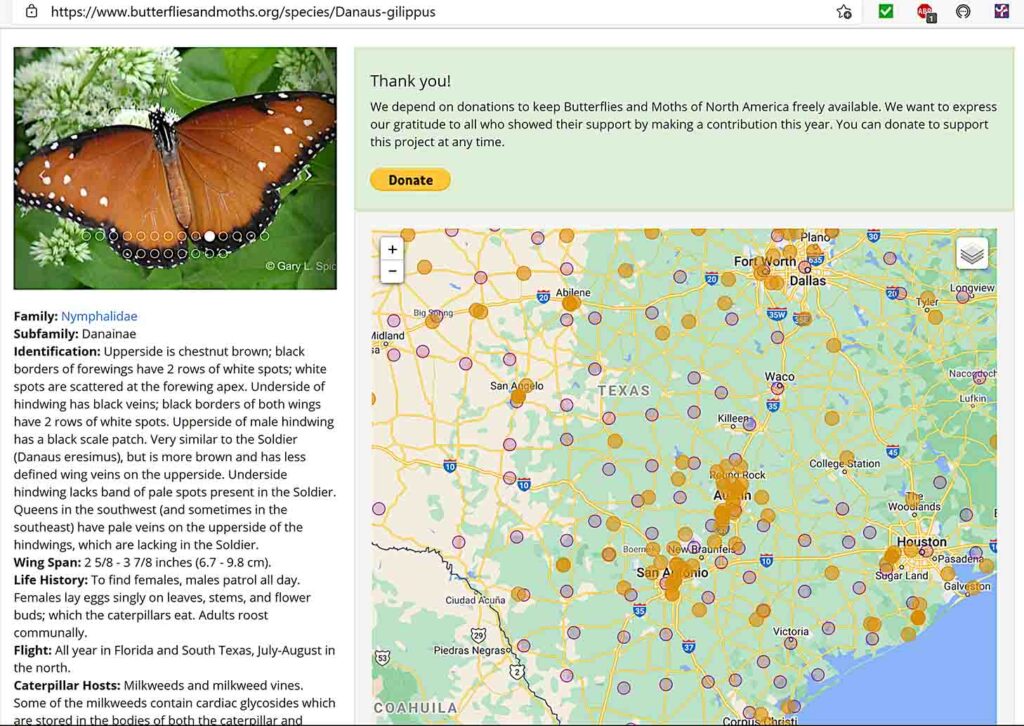

Results for the Queen (Danaus gilippus, https://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/species/Danaus-gilippus) include general description, caterpillar hosts, and much more. Under “caterpillar hosts” you’ll see that Queen caterpillars also consume milkweed. BAMONA includes a zoomable map with historical reports of Queen sightings. Clicking on individual sightings often brings up additional photographs. You may also want to add a column in your chart to note what pollinators would visit each plant on your list.

Another way to build pollinator plant lists.

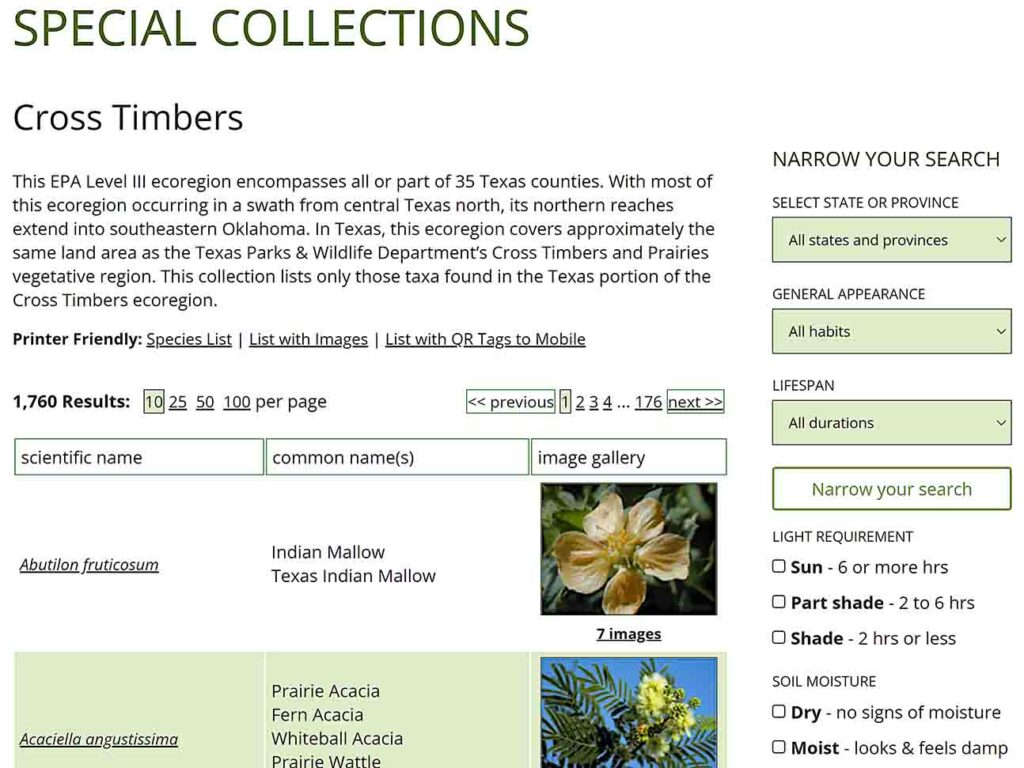

Fortunately, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center offers lists for various pollinators. From their homepage, hover your cursor over “Native Plants” to produce a dropdown list that includes “Plant Lists.” Click on that to navigate to the “Plant Lists & Collections” page (https://www.wildflower.org/collections/). At the top of the page are “Recommended Species by State.” Texas is a huge state with many climate and soil zones, each with its own list of native plants adapted to those conditions, so it’s fortunate that Lady Bird links to lists of “Plants for Central Texas” as well as for other ecoregions like Edwards Plateau, High Plains, and Western Gulf Coast Plain. These lists help narrow your search for likely winners. For example, Austin area people can search a list called Texas-Central Recommended” (https://www.wildflower.org/collections/collection.php?collection=TX_central), while Southwest Texas residents can search the Southwestern Tablelands collection (https://www.wildflower.org/collections/collection.php?collection=er26).

Each collection includes the same search parameters discussed above, so you may search for annuals or perennials that prefer sun or part-shade, and dry or moist soil. You can narrow your search further by selecting criteria like bloom time and size, then check the resulting list against the USDA plant database to verify which plants are native to your county.

Scrolling farther down the “Plant Lists & Collections” page, you arrive at the “Plants for Pollinators” section. Clicking on “Butterflies and Moths of North America” returns a list of nectar and larval hosting plants (https://www.wildflower.org/collections/collection.php?collection=bamona). Again, you can cross-reference these plants against the USDA plant database to find your county’s natives. The good news is that if a plant is native to your county, there are native pollinators visiting it; otherwise, that plant wouldn’t survive. As with other specialty pages, you can narrow your search by selecting criteria like light requirements, soil moisture, bloom time, and height.

Lady Bird’s “Plant Lists & Collections” page also provides special collections for other pollinators, including native bees and bumble bees. Clicking on any of these links returns a page offering the same features of narrowing your search via cultural criteria like light requirements and size, as discussed above.

Other resources available

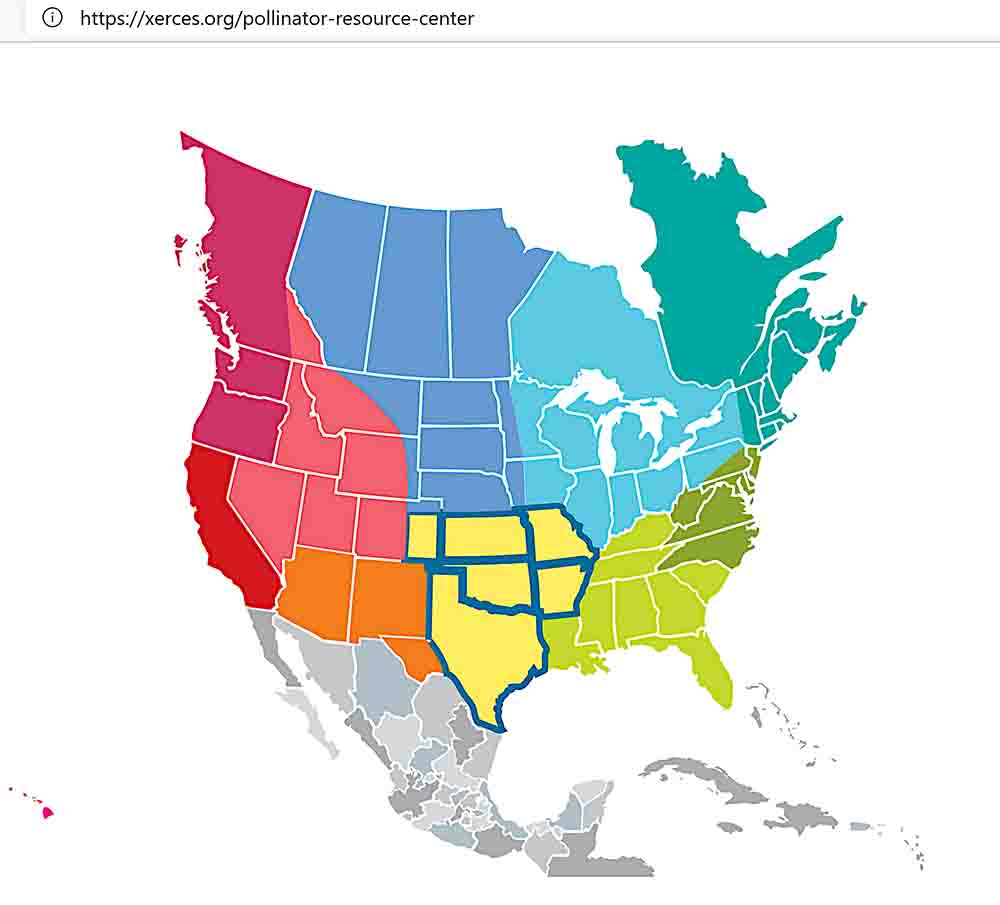

Consider one final resource here: The Xerces Society also offers lists of pollinator-friendly plants (https://xerces.org). Hovering your cursor over “Resources” produces a dropdown list including “Pollinator Conservation Resource Center”. Clicking that link brings you to a page containing lists of “region-specific collections of publications, native seed vendors, and other resources to aid in planning, establishing, restoring, and maintaining pollinator habitat…” (https://xerces.org/pollinator-resource-center)

The page includes a map where you can click on the region including Texas. Clicking there returns their resource page that includes many resources like habitat assessment, and native seed and plant vendors (https://xerces.org/pollinator-resource-center/south-central). It also includes “Plant lists”. Clicking the green “Click to Expand” banner opens links to documents and resources.

Clicking on “Pollinator Plants: Southern Plains” navigates to a page containing the document entitled “Monarch Nectar Plants: Southern Plains” (https://xerces.org/publications/plant-lists/monarch-nectar-plants-southern-plains). There, you can download a list of nectar plants, organized by criteria like blooming season and water needs. Since this list is for the Southern Plains, you’ll need to cross-reference the USDA plant database to determine if a plant is native to your county.

Clicking on “Pollinator Plants for Texas Conservation Practices” returns another document published by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), which offers a “list of pollinator friendly plants for use in conservation practices in Texas…” (https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_PLANTMATERIALS/publications/txpmctn8222.pdf) It contains alphabetized lists of herbaceous and woody species that you can cross-reference with Lady Bird and the USDA plant database to produce another list of best-performing plants for your garden.

Rather than letting others limit your garden design—and pollinator visitors—accessing these resources and following this process empowers you to create a design using native plants to attract pollinators for the most attractive, low-maintenance garden possible.

Howard Nemerov is a Texas Certified Master Gardener in Bastrop County, specializing in low-maintenance, high-pollinator gardens.